This article serves as an expanded section of the preceding article.

How Memory Works in the Human Brain

The human brain is a master of efficient, adaptive memory storage. Modern neuroscience reveals that memory is not localized to a single region but is distributed across interconnected networks, with mechanisms that balance plasticity (learning) and stability (retention). Key principles include:

- Synaptic Plasticity:

- Hebbian Learning: “Neurons that fire together wire together” — synapses strengthen when pre- and post-synaptic neurons activate simultaneously (Hebb, 1949).

- Long-Term Potentiation (LTP): Repeated activation strengthens synaptic connections, critical for long-term memory (Bliss & Lømo, 1973).

- Hippocampal Role:

The hippocampus acts as a “memory index,” organizing and consolidating short-term memories into long-term storage in the neocortex (Squire, 1992). - Sparse and Distributed Encoding:

Memories are stored across overlapping neural ensembles, allowing efficient recall and robustness to damage. For example, a single neuron might participate in multiple memories (Quiroga et al., 2005). - Forgetting as a Feature:

The brain prunes less-used connections to prioritize relevant information, a process mirrored in AI techniques like dropout or network pruning.

Comparing Artificial and Biological Memory Systems

| Aspect | Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) | Human Brain |

|---|---|---|

| Storage Mechanism | Information is stored in synaptic weights and activation patterns (e.g., LSTM cell states). | Distributed synaptic strengths and neural ensemble firing patterns. |

| Learning Rule | Backpropagation adjusts weights to minimize loss. | Hebbian plasticity, spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP), and neuromodulators (e.g., dopamine). |

| Energy Efficiency | Computationally expensive; requires significant resources for training. | Extremely efficient (~20W power consumption for the entire brain). |

| Memory Consolidation | Requires explicit retraining or replay buffers (e.g., experience replay in reinforcement learning). | Sleep-dependent consolidation, where memories are reactivated and stabilized during rest. |

| Robustness | Fragile to adversarial attacks or parameter pruning. | Resilient due to redundancy and distributed encoding (e.g., surviving stroke damage). |

| Scalability | Struggles with catastrophic forgetting when learning sequentially. | Naturally supports lifelong learning through neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity. |

Lessons from Neuroscience for AI

- Sparse Activation:

The brain’s sparse coding (e.g., <1% neurons active at any time) minimizes energy use. ANNs could adopt sparsity constraints, as seen in models like Sparse Neural Networks. - Dynamic Synapses:

Biological synapses change strength based on usage (e.g., short-term plasticity). AI models like Differentiable Plasticity mimic this for adaptive memory. - Neurogenesis:

The brain grows new neurons in the hippocampus to integrate fresh information. AI systems could explore dynamic neuron addition, as in Growing Neural Networks. - Sleep-Inspired Learning:

Simulating “offline” memory replay during training could improve retention, akin to biological consolidation (Parisotto et al., 2020).

Case Study: Transformers vs. Hippocampal Indexing

Transformers, with their self-attention mechanisms, parallelize sequence processing by weighing relationships between tokens. This resembles the hippocampus’s role in linking contextual details (e.g., time, place) to form episodic memories. However, unlike transformers, the brain does not process all past inputs equally; it prioritizes salient events (e.g., emotions enhance memory retention).

Implications for the Research Project

- Bio-Inspired Architectures:

Hybrid models combining LSTM-like gating with attention could mimic the brain’s balance of recurrence and parallel processing. - Efficiency Metrics:

Measure memory efficiency not just by neuron count, but by energy use or robustness to “synaptic” damage (e.g., randomly zeroing weights). - Lifelong Learning:

Incorporate neurogenesis-like mechanisms to dynamically expand networks without forgetting prior knowledge.

Academic References for Brain-ANN Comparisons

- Neuroscience of Memory:

- Kandel et al. (2000). Principles of Neural Science.

- Bio-Inspired AI:

- Hassabis et al. (2017). Neuroscience-Inspired Artificial Intelligence.

- Sparse Coding:

- Olshausen & Field (1996). Emergence of Simple-Cell Receptive Field Properties.

Conclusion

By studying memory in both artificial and biological systems, this research aims to bridge gaps between neuroscience and machine learning. Insights from the brain’s efficiency, adaptability, and robustness could revolutionize how we design neural networks — moving us closer to models that learn, remember, and generalize as elegantly as humans do.

Next Steps:

- Experiment with brain-inspired plasticity rules in ANNs.

- Compare catastrophic forgetting in ANNs to natural forgetting in humans.

Expanded Section: Reinforcement Learning vs. Human Learning Strategies

How Humans Learn New Skills

When humans learn a task—whether riding a bike, solving math problems, or playing chess—they follow a structured, iterative process rooted in neuroscience and cognitive psychology:

- Focused Attention:

- Spotlighting: The brain’s prefrontal cortex directs attention to specific aspects of a problem (e.g., balancing on a bike before pedaling).

- Chunking: Breaking complex tasks into smaller, manageable parts (e.g., practicing chess openings separately).

- Correlation Hunting:

- Pattern Recognition: The brain identifies relationships between actions and outcomes (e.g., “leaning left helps me turn left”).

- Hypothesis Testing: Trial-and-error adjustments refine understanding (e.g., testing different grip strengths when learning to throw a ball).

- Repetition and Imitation:

- Mirror Neurons: Observing and mimicking experts (e.g., copying a teacher’s handwriting) activates neural circuits that simulate the action (Rizzolatti & Craighero, 2004).

- Deliberate Practice: Repeating tasks until they become automatic (e.g., scales on a piano).

- Generalization and Automation:

- Procedural Memory: Skills shift from conscious effort (prefrontal cortex) to subconscious execution (basal ganglia), creating “muscle memory” (Squire, 2004).

- Neuroplasticity: Repeated practice strengthens synaptic pathways, physically rewiring the brain’s structure.

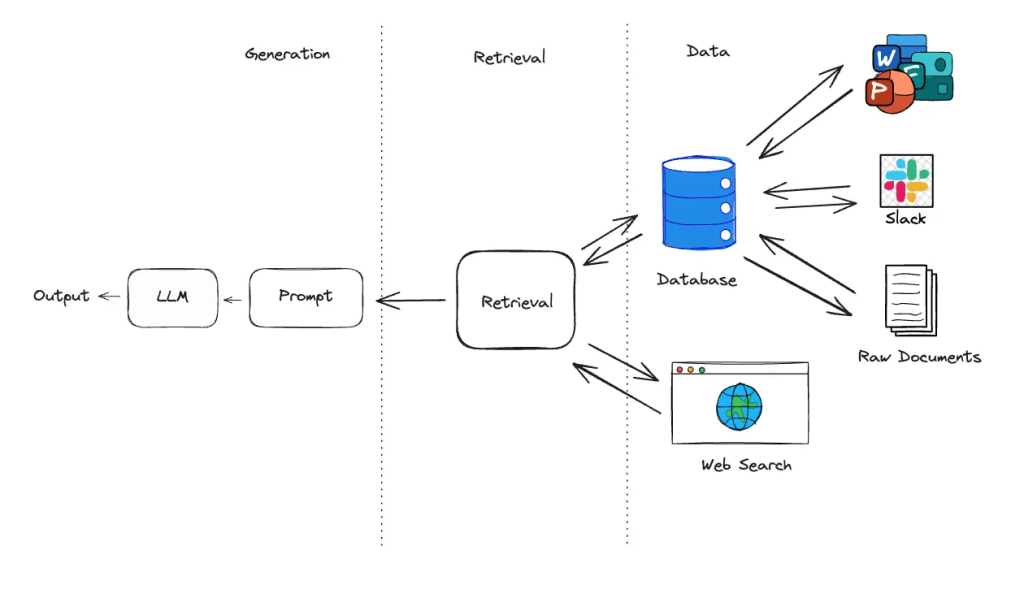

How Reinforcement Learning (RL) Works

Reinforcement learning mimics trial-and-error learning in humans but operates through mathematical optimization:

- Exploration vs. Exploitation:

- The RL agent balances trying new actions (exploration) and leveraging known rewards (exploitation).

- Reward Signal:

- Analogous to dopamine-driven feedback in the brain, rewards reinforce desirable behaviors.

- Policy Optimization:

- The agent refines its strategy (policy) to maximize cumulative rewards, often using algorithms like Q-learning or policy gradients.

- Generalization:

- Trained models apply learned behaviors to unseen scenarios (e.g., a chess AI facing a novel board position).

Illustration: Reinforcement Learning Loop

Key Similarities and Differences

| Aspect | Reinforcement Learning (AI) | Human Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Goal | Maximize cumulative reward. | Achieve mastery, often driven by intrinsic motivation (curiosity) or extrinsic rewards (praise). |

| Feedback | Sparse, delayed rewards (e.g., winning a game). | Rich, multimodal feedback (sensory, emotional, social). |

| Focus Mechanism | Attention layers or curriculum learning prioritize critical states. | Prefrontal cortex directs attention to relevant task components. |

| Error Handling | Adjusts policy via gradient descent on loss functions. | Learns from mistakes through metacognition (“What went wrong?”). |

| Generalization | Requires explicit techniques like transfer learning or meta-learning. | Naturally generalizes by abstracting principles (e.g., applying algebra rules to new problems). |

| Automation | Converges to a fixed policy; lacks true “hardwiring.” | Skills become automatic via myelination (faster neural pathways) and synaptic pruning. |

Case Study: Learning to Play a Video Game

Human Approach

- Focused Attention: Watch a tutorial to learn controls (spotlighting).

- Correlation Hunting: Notice that “jumping avoids enemies.”

- Repetition: Practice the jump timing in a safe zone.

- Automation: React to enemies instinctively after hours of play.

RL Agent Approach

- Exploration: Randomly press buttons to discover actions.

- Reward Signal: Receive points for defeating enemies.

- Policy Update: Use Q-learning to prioritize attack actions.

- Generalization: Deploy the policy on unseen game levels.

Neuroscience Insights for Improving RL

- Intrinsic Motivation:

Humans learn driven by curiosity, not just rewards. RL agents could incorporate curiosity modules (Pathak et al., 2017) to explore novel states. - Meta-Learning:

The brain rapidly adapts to new tasks by reusing prior knowledge. Meta-RL frameworks like MAML mimic this “learning to learn” ability. - Emotional Feedback:

Emotional salience (e.g., fear of failure) sharpens human memory. RL could weight experiences with high reward variance more heavily. - Sleep-Inspired Replay:

Humans consolidate memories during sleep. RL systems could use offline replay buffers to reinforce critical experiences (Mattar & Daw, 2018).

Implications for the Research Project

- Dynamic Attention:

Implement attention mechanisms that mimic human spotlighting to prioritize critical input characters. - Curriculum Learning:

Train networks on progressively harder text reconstruction tasks, akin to human skill scaffolding. - Hardwiring via Sparsity:

Encourage sparse, stable synaptic pathways (e.g., Lottery Ticket Hypothesis) to simulate procedural memory. - Neuromodulation:

Simulate dopamine-like signals to reinforce successful memory retention in neural networks.

Academic References

- Reinforcement Learning:

- Sutton & Barto (2018). Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction.

- Neuroscience of Learning:

- Doya (2000). Reinforcement Learning in the Brain.

- Skill Automation:

- Graybiel (2008). Habits, Rituals, and the Evaluative Brain.

Conclusion

While reinforcement learning systems excel at optimizing for rewards, they lack the rich, adaptive learning strategies of the human brain. By integrating neuroscience principles—such as dynamic attention, intrinsic motivation, and memory consolidation—this research could unlock neural networks that learn more efficiently, generalize more robustly, and even “hardwire” skills in ways that mirror biological intelligence.

Next Steps:

- Experiment with dopamine-inspired reward signals in text reconstruction tasks.

- Compare curriculum learning against traditional RL training for memory retention

Reviewed and published by Simon Heilles.

Leave a comment